Food & community in prison

We asked ten people incarcerated at Fishkill Correctional Facility to tell us about the circumstances under which food is shared and builds community, and how food can just as easily break trust.

Food builds bonds. This simple axiom proves true in every culture I know of, even the prison culture I've lived in for the past 22 years. Foodways both create and sustain culture, and they also serve as portals for people to experience new cultures. For instance, a cuisine that I've come to especially appreciate is Latino/a food, especially arroz y frijoles (rice and beans). Cooked by steaming out added water, the rice develops a burnt bottom layer in the pot that can be scraped out and served with the fluffier rice. This burnt rice, known as ‘pegao’ in Puerto Rican Spanish or ‘concon’ in the Dominican dialect, is scorned by some, but cherished by many others. For myself, a Slavic American of Ukrainian, Polish, and Croatian descent, I've come to love and crave this part of the dish so much that I'll often eat pegao that others are about to throw away. Its awesome texture and flavor (the pegao is infused with the spices and oils that have been added to the rice while it is steaming) are the main reason, but it also represents a bond I've forged with men who were part of a culture I knew nothing about before I came into prison.”

- Jared

As Jared describes, food is a central part of prison culture and the cultures of the people incarcerated there, but food builds bonds across the divide between inside and outside prison as well. As people with loved ones in prison, we are used to sharing food through assembling food packages1 and splitting vending machine sandwiches, little bags of potato chips, and packages of M&Ms in the visiting room. Jared and Jonathan also often share stories with us about cooking and eating in prison, and we’ve often been surprised, moved, and occasionally even bowled over with laughter by their relationships to and through food.

As we reflected on our experiences and the experiences of our loved ones, we were especially interested in the ways food intersects with trust, often building it but sometimes betraying it.

The breaking of bread can both reinforce and resist the normal operations and politics of prison. We asked ten people incarcerated at Fishkill Correctional Facility to tell us about the circumstances under which food is shared and builds community, and how food can just as easily break trust. Through their stories, it was clear that food is a central way that friends in prison show affection, care for each other, and fight against the isolation a prison sentence is meant to impose. When shared with others, a person’s food can be a major source of pride when a recipe is perfected or a dish comes out well. On the other hand, food can also be a source of tension and a mark of inequity.

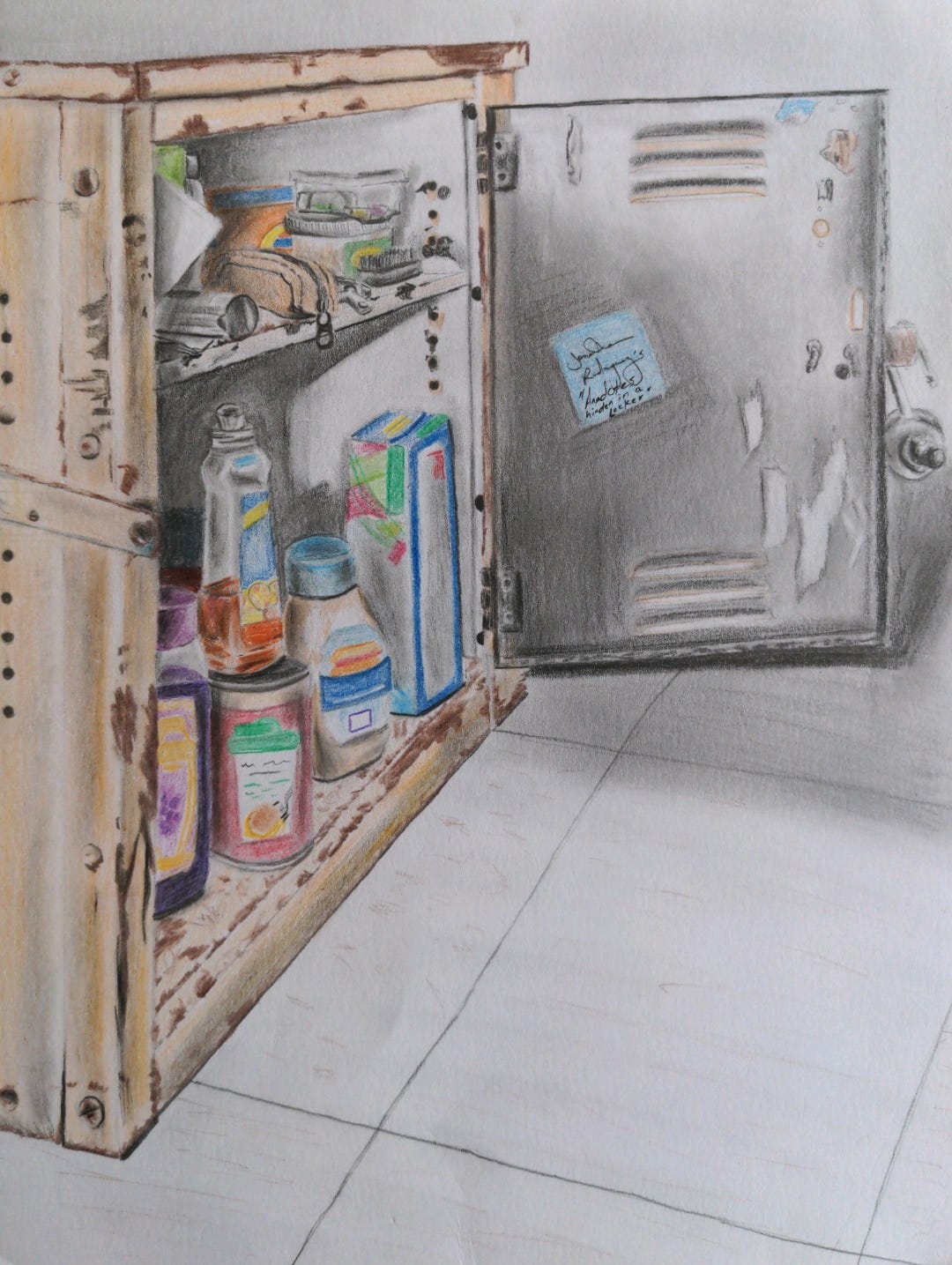

The majority of people in prison could fit the criteria for being classified as food insecure, defined by the United States Department of Agriculture as, “a lack of consistent access to enough food for every person in a household to live an active, healthy life.” This is because the food served in prison mess halls, although technically “adequate” (in terms of calories) is often inedible due to its poor quality and tendency to be spoiled at the time it is served. Given the uneven access to high-quality, nutritious food, with only some incarcerated people receiving (grossly overpriced) food packages from prison vendors2, food-sharing can be complicated and fraught with feelings of unfairness or scarcity.

Many people choose to form food partnerships with other trusted individuals as a way to pool and save resources. If a person receives a food package and/or money from home, he is more likely to cook his own meals. If a person without resources wants to avoid the hassle of going to the mess hall (read more about that here), there are other ways that they can “pay” for their food, whether it’s as simple as helping someone with their school work, or as fraught as being willing to come to a person’s physical defense. George told us that because of the possible strings that can come attached to a meal, “accepting food from someone requires a level of acceptance, trust, and solidarity with that person.” Someone’s reputation is a big part of the decision whether or not to share food with them, as George explained, “usually if you’re new to a prison guys will observe you for a couple of weeks and speak to people who were in other prisons with you.”

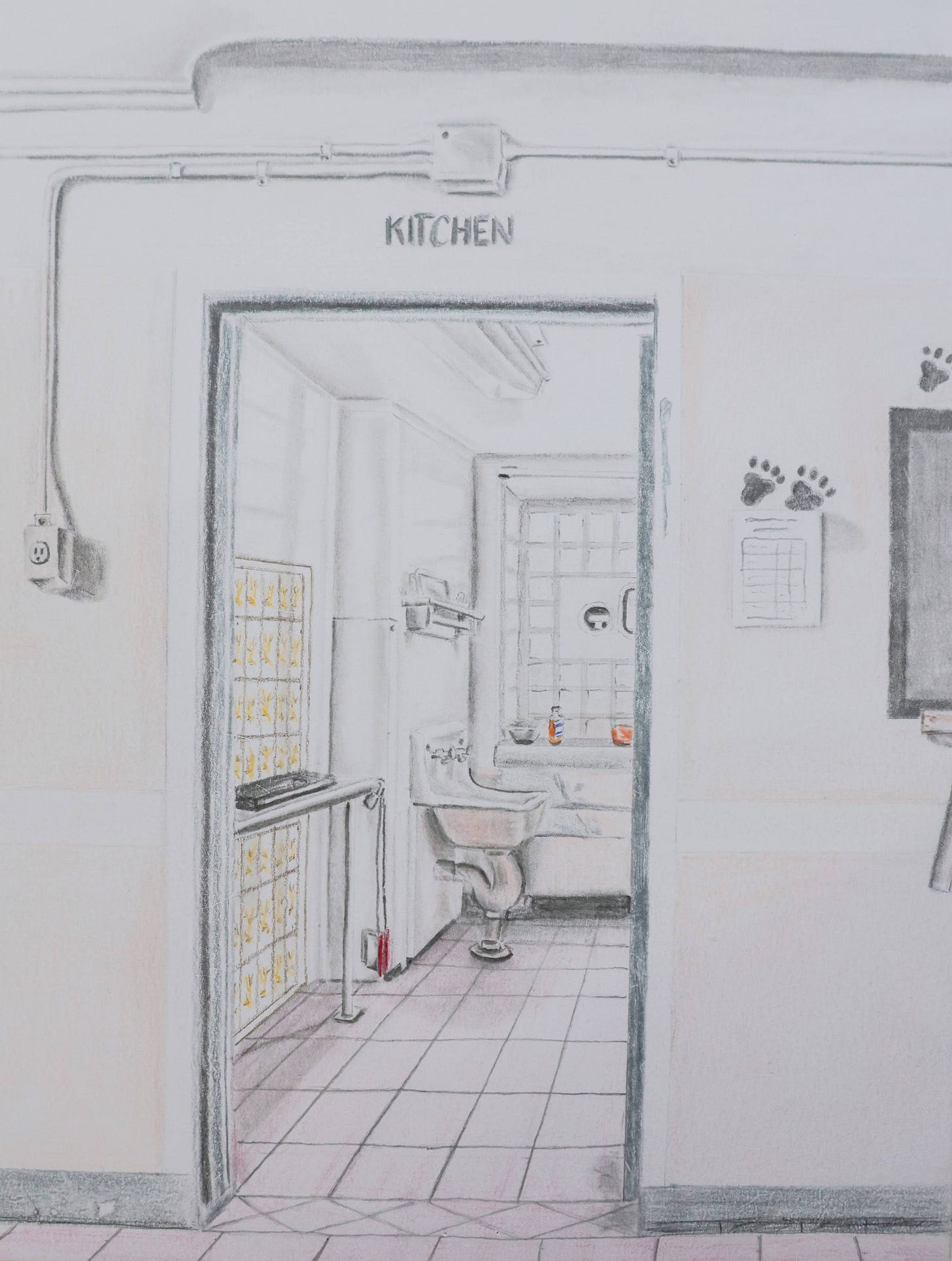

Cooking a meal can take hours and multiple equipment and ingredient workarounds, so it’s not surprising that sharing food in prison can be a more serious undertaking than it generally is outside of it. In order to cook with very limited equipment, people in prison have to be inventive. For most chefs, a knife is the most important piece of equipment, but as you may expect, there are no knives to be found in the kitchens in prison housing units or cells. Incarcerated people can often be found using items like can tops to cut produce and chip bags stuffed with food and tied to radiators as a method of baking. A friend once even told one of us the story of how he baked an apple pie in solitary confinement by stripping the paint off the metal bed frame and using lit paper underneath the metal to heat the surface like a skillet.

Chris shared, “As someone who considers himself a bit of a foodie on the street and a pretty damn good prison chef: necessity really is the mother of invention. I have seen some amazing food dishes put together in prison that would impress a Michelin-star chef at home. I personally did some impressive dishes with a #9 tuna can, a rigged eye, and a rigged hot pot, like curry mackerel stew over coconut rice with peanut dipping sauce.” Josh told us, “I used to make a peanut butter square/cookie that I wrapped in dough and fried. I called them “dookies” because they were a donut cookie. Everybody loved them, everybody hated the name.”

Embedded in these stories is the importance of sharing successes–and cooking hacks–with others. During holidays, particularly Thanksgiving, the communal nature of meal-sharing is especially significant and the rules around who can participate in food partnerships seem to fade, if only for the day. Tyler explained, “At my old prison on Thanksgiving and Christmas there was a few different groups of people that would cook huge meals separately and all share. If anyone wasn’t included or couldn’t put food in or simply didn’t have, we always fed everyone in the house.” Though they’re unable to be at home with their families, many incarcerated people create strong, family-like bonds with their friends and use the holidays as a way to express their love for those people. Johnny told us, ”I cook not for me, but for my dear friends. Being the least prone to show affection, I find it possible to express my adoration through the foods I create and cook.”

However, food partnerships can quickly become strained or broken when a person perceives that they are being taken advantage of. Josh and Peter shared that in situations where people were blatantly caught stealing, making “selfish portions” or “act[ing] stingy with coveted items,” they were breaking the trust needed to maintain a healthy cooking partnership. Additionally, if an incarcerated person finds unexpected food, especially candy, on their bed, it often begins an immediate search to find out who put it there. Jonathan explained, “Candy on your bed can mean two things in prison: the original meaning behind this gesture was a subtle way to indicate sexual interest in another man that implies a threat of rape, but it’s also commonly done as a playful joke between good friends.” This joke appears to be one that people repeat often, and even get creative with. Tyler shared, “Everyone knows what candy on the pillow means. I used to get fancy-flavored Hershey’s Kisses and would sneak them on friends pillows and laugh over them bugging out for a second. They always knew I was just getting a laugh.”

The stories shared by those at Fishkill Correctional Facility highlight the complexities of food-sharing in prison. Food can be a symbol of camaraderie, trust, and resourcefulness, but it can also lead to feelings of inequality and conflict in an environment where resources are limited. For us, with people we love in prison, food is an equally important way to show care and affection, but it is also often weighed down with the pain of separation. For one of us, seeing the Trader Joe’s jelly beans I used to send in packages always makes me feel sad, especially because they were always the source of some lighthearted teasing: “Make sure you share the jelly beans with Country and Josh and don’t eat all eight boxes yourself!” For the other, it’s a sense of loss over picking up an item in the grocery store, and knowing it’s going to be that same item that gets tucked inside a prison locker. I couldn’t get inside to help cook dinner, but the food I held in my hands used to make that journey.

We hope that this reflection will help to open up the often hidden world of daily life, friendship, and food in prison, but we also hope it illuminates the ways in which the prison system creates scarcity, vulnerability, and tension around food–and how reinstated packages and better institutional food quality could improve the health and safety the people we love and, in turn, the friends they love, behind the wall.

In May 2022, the New York Department of Correction and Community Supervision halted incarcerated people’s ability to receive food packages from their loved ones. These packages could include fresh fruits and vegetables, canned goods, and vacuum-sealed items. See: https://www.vera.org/news/change-for-the-worse-life-under-new-york-doccss-new-package-policy

Under the new package policy, incarcerated folks can receive food packages from approved vendors, all of whom charge higher prices for items than you would pay in a typical grocery store. There is also the added cost of shopping.

This was such an interesting topic. Thank you for sharing!