Pistachio shell resistance: introducing a series about food in New York State Prisons

Exploring how food is used to punish and diminish the humanity of those serving their sentences.

“Shells,” said Jonathan, as he saw me opening the bag of pistachios and placing it between us on the visiting room table.

“What?” I asked, looking at him until my brain caught up. “Oh…weird,” I added.

We held the shells in our hands, running our fingers along the edges. It was the first time I’d ever appreciated how hard they are and fully contemplated the reason behind them being banned.

To most people, the sight of pistachios in their shells is nothing to think twice about, but according to New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS) Directive #4911, incarcerated individuals are not allowed to have any nuts in shells. While it isn’t explicitly stated in the directive, we presume authorities are concerned that the hard shells could be sharpened and used as a kind of weapon that would be undetectable by a metal detector.

The unshelled bags of pistachios must have accidentally made their way into the vending machine in the Fishkill Correctional Facility visiting room. It was an oversight that immediately caught Jonathan’s attention.

That’s not the only food that isn’t allowed in New York State prisons; the list of regulations for food is seemingly endless.1

For example, you won’t find a Dark Chocolate KIND bar, cinnamon raisin bread, or any flavor of Pringles. Each of these items poses a security threat to the facility, some real, some perhaps exaggerated.

Many products made with chocolate contain an ingredient called “chocolate liquor”, which despite the name, has no alcohol in it, or relation to alcohol. But because alcohol is prohibited in prisons, any product with this ingredient gets banned too. This feels a bit silly when applied to items like KIND bars, which I’ve never seen someone become drunk from consuming.

Cinnamon raisin bread seems innocent enough, but dried fruits are limited to very small quantities, related to concerns that they will be used to make alcohol.2 So any kind of product with dried fruit, like cinnamon raisin bread or a granola bar with dried cranberries, in which the exact quantity of dried fruit is a mystery, is off-limits.

In the case of Pringles, it’s not the chips themselves that are the problem (unless the crime is for poor taste, because they certainly win that category in my book), it’s the packaging. Pringles have a peel-off lid, and anything with that kind of “peel-back” packaging isn’t allowed. Oreo cookies in their usual packaging are another example. This is due to concerns that the peel may have been removed and then re-glued as a way to introduce drugs into the facility.

When you combine these rules with the rest included in Directive #4911 (and those that need to be learned from “experience”, a.k.a. sending food that gets denied entry to the facility), it becomes very difficult to put together a package of acceptable foods to send to someone in prison.3 This is part of a larger problem.

Controlling incarcerated individuals’ experiences with food and eating in the name of security and safety is just one way that prisons try to punish and diminish the humanity of those serving their sentences.

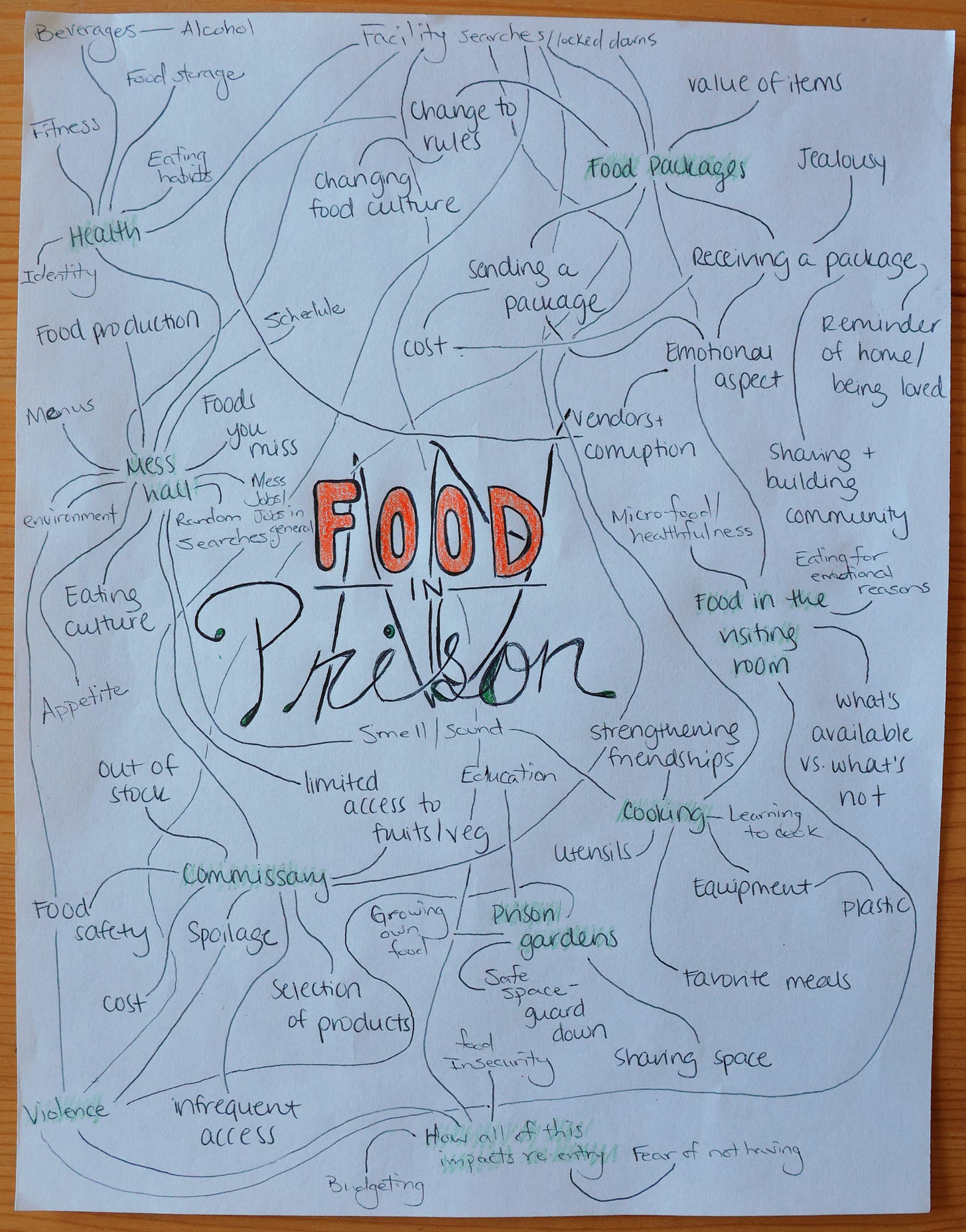

This series will explore many topics that fall within the umbrella of food in prison and discuss the broader implications of the prison food environment. We hope that it will give you a greater understanding of why prisons are fundamentally problematic institutions.4

“You know, this is the first time I’ve ever had pistachios in the shells,” said Jonathan.

As we sat there with the pile of empty shells laid out on the table in front of us, we couldn’t help but smile at the tiny bit of resistance they represented.

Recommended watching: Ally vs. Co-Conspirator

Jonathan has nearly 20 years of lived experience of being incarcerated and is co-authoring this series. Check out some of his other work that has been published by The Harbinger, a publication of The N.Y.U. Review of Law & Social Change.

Additionally, there are many individuals and organizations that we’d like to shout out for contributing to our learning (we probably forgot some, we’ll work on a more comprehensive resource list eventually):

The countless currently and formerly incarcerated individuals that both of us have had the opportunity to interact with. And the friends, family members, and otherwise loved ones of incarcerated individuals that are part of our circle. We’re hoping you’ll have the chance to hear from many of them in this series as well.

Impact Justice: Eating Behind Bars: Ending the Hidden Punishment of Food in Prison

Maryland Food & Prison Abolition Project: "I Refuse to Let Them Kill Me": Food, Violence, and the Maryland Correctional Food System

Who Speaks for Me? Non-Profit Organization

Works of: Mariame Kaba, Clint Smith, Ian Manuel

In addition to the official rules stated in Directive #4911, there are other rules that must be learned through word of mouth. For example, the directive does not state anything about breakfast cereals (which are served in the mess hall), but those are not allowed to be sent via food packages. Jonathan added that this ambiguity helps give the facilities even more power to make decisions to deny food.

Some people still manage to make alcohol in prison since you don’t actually need dried fruit to get the job done.

New York is the only state in the country that allows food packages, but they’ve recently made it more difficult and expensive to do with Directive #4911A. You can read more about that in an open letter that a group of us wrote here.

Interesting! Excited to see more from this series. Also I hate Pringles so thank you for that!